Roxanne Thiara was born in Manitoba, Canada. She spent most of her childhood in Quesnel, British Columbia, under the foster care of Mildred Thiara and her family of three. Eventually, Mildred was granted legal guardianship of Roxanne.

"She was quite a good kid – a really happy, bubbly kid," recalled Mildred.

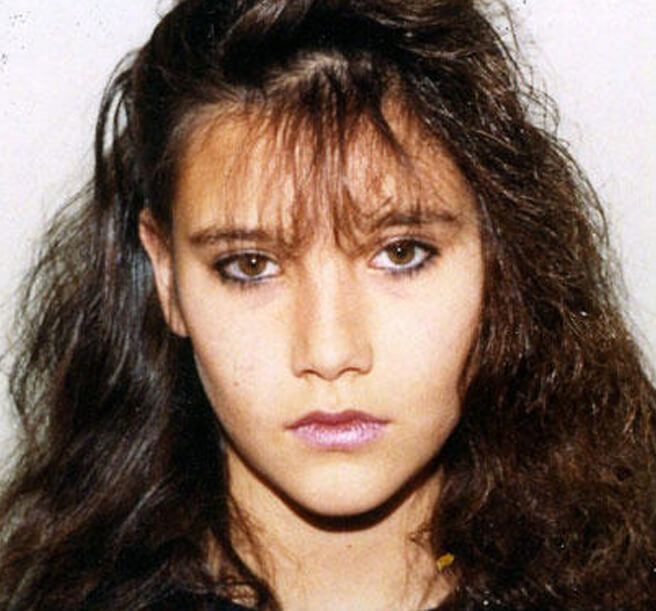

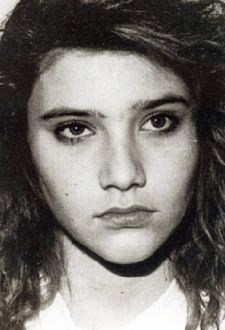

Roxanne Thiara (The Vancouver Sun)

As a teenager, Roxanne began struggling to attend school regularly and started associating with a crowd that Mildred described as a "bad bunch." At the age of twelve, Roxanne was incarcerated in a youth detention center for an unknown petty offense. While there, she befriended another girl, Kristal Grenkie, who remembered Roxanne as just a young and innocent child. Roxanne’s former brother-in-law, Rene Beirness, said the incarceration was "the worst thing that happened to her" and that after her release, "she went wild."

Following her release, Roxanne spent most of her time in Williams Lake, a town just outside Quesnel. Struggling to reintegrate, she turned to drugs and engaged in survival sex, a form of sex trafficking, to survive.

Despite these difficulties, Mildred recalled Roxanne stopping by her house or calling every few days. Her family kept faith that Roxanne’s life would improve. In late June 1994, Roxanne even told Mildred that she wanted to enter rehab to overcome her addiction. She had always dreamed of becoming a fashion designer and hoped to pursue a better life. She made an appointment to enter a drug treatment program.

On June 27, 1994, Roxanne left Mildred’s house in Quesnel to return to Prince George to collect her belongings. She told Mildred she would return the next day. That was the last time Mildred ever heard from or saw Roxanne, as she never returned to Quesnel. Shortly thereafter, during a long weekend in July, Roxanne told a friend she was going out with a customer in downtown Prince George. She walked around the corner of a building and was never seen again. Throughout July, Mildred searched and called around, hoping for any sign of Roxanne. Flyers were distributed, and Roxanne was officially reported missing, but no news surfaced.

On August 17, 1994, approximately one month after her disappearance, Roxanne’s body was found in the bush along Highway 16, just outside the town of Burns Lake. She had been murdered at the age of 15.

When she did want to change, she wasn't given the chance.Mildred Thiara, legal guardian of Roxanne Thiara (Highway of Tears)

After her body was found, police released Roxanne’s photo to the public, hoping someone would come forward with information. They received nearly forty tips following the release. Authorities believed Roxanne had been murdered elsewhere and that her body was left alongside Highway 16. They suspected the killer was familiar with the area.

We're still having a hard time coming to terms with everything. She was a well-loved little girl; she was well-adored.Mildred Thiara, legal guardian of Roxanne Thiara (Highway of Tears)

The family held a small funeral to honor Roxanne’s life. Unfortunately, the tips did not lead police to her killer. Since Roxanne’s disappearance, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) established a task force called E-PANA to investigate a series of unsolved murders along Highway 16, including Roxanne’s case. The task force’s purpose is “to determine if a serial killer, or killers, is responsible for murdering young women traveling along major highways in BC” (E-PANA website). To date, however, Roxanne’s case remains unsolved, as do all the cases along the highway included in E-PANA.