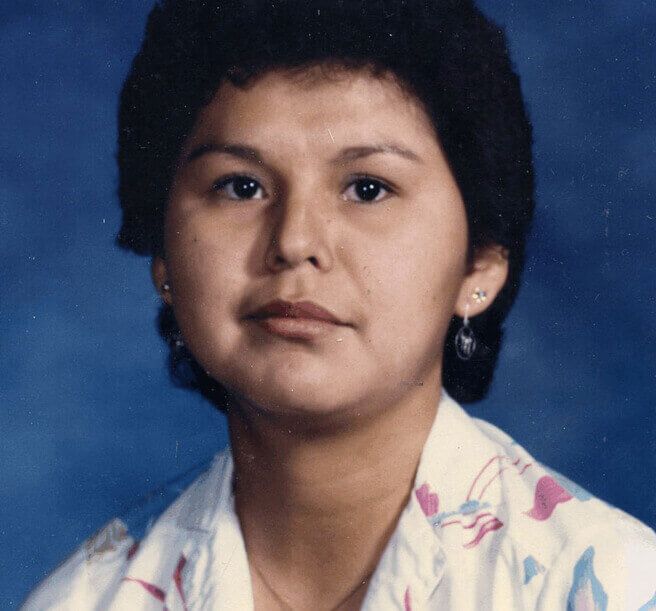

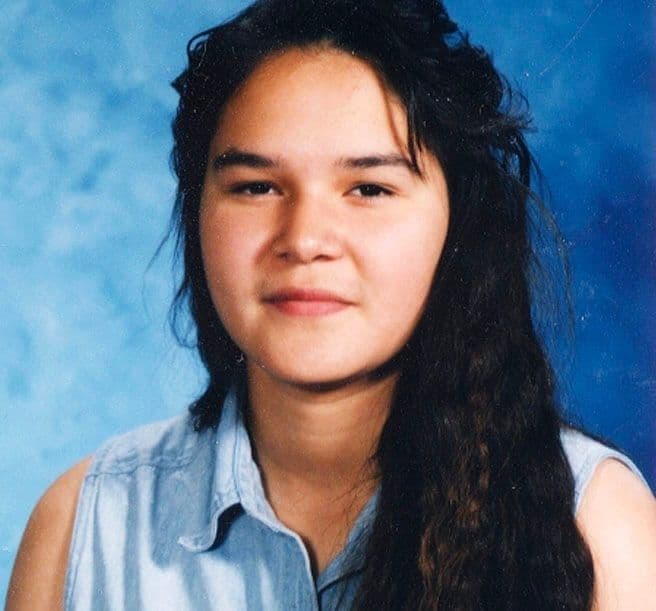

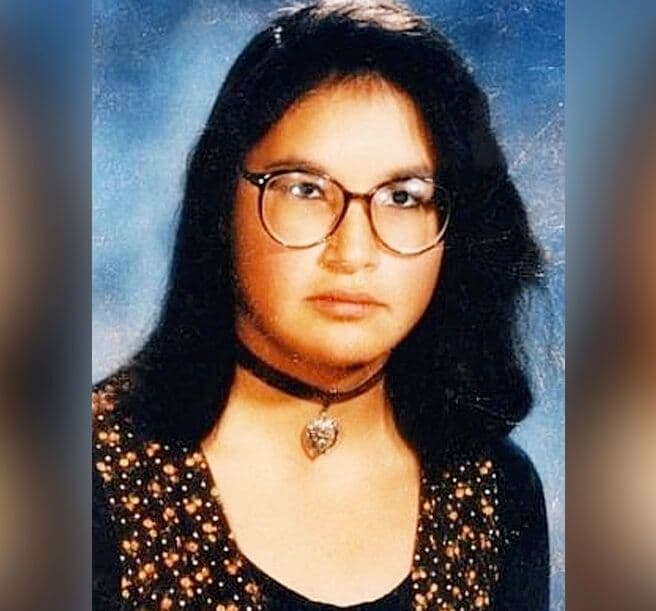

Alberta Williams was a member of the Gitksan Tribe from Gitanyow, British Columbia. She lived a relatively quiet life during her childhood; her father, Lawrence, drove logging trucks, and her mother, Rena, stayed home to care for Alberta and her siblings. They were a very close-knit family. Alberta was known as a kind and shy child. As she grew older, she became known as a caring person who loved life and viewed the world as a good place, content with whatever came her way. Her siblings sometimes thought she trusted people too much and were always a little extra protective of their sister.

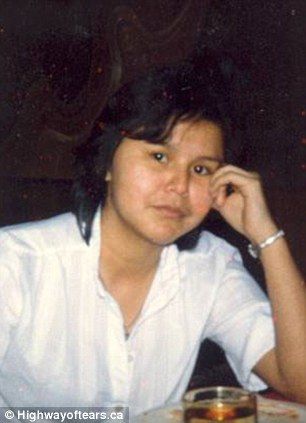

Alberta Williams (Justice for Native Women)

Each spring, the Williams family would visit the coast where Alberta’s father worked as a fisherman and her mother worked in the canneries. The family moved from Gitanyow to Prince Rupert. Soon after, Alberta’s sister Claudia moved to Vancouver, and Alberta’s parents sent each of their children to stay with Claudia so they could attend high school there. Her parents wanted their children to get a good education and experience more than what a small town could offer. Both sisters finished high school, began working, and soon started sharing an apartment in downtown Vancouver.

In Vancouver, it is not uncommon for residents to leave the city and head north for seasonal jobs. Alberta and Claudia usually went to Prince Rupert for positions at the B.C. Packers plant, a popular salmon cannery. The work was hard, but after a couple of months, the two sisters would return to Vancouver well paid.

In 1989, Alberta was 24 years old and living in Vancouver with her fiancé. It was nearing the end of the summer, and she was preparing to head back home from the seasonal work in Prince Rupert. She was looking forward to starting a new job as a waitress and had plans to enroll in college.

Friday, August 25th, marked the last day of work for Alberta and Claudia at the cannery. The sisters planned to go to Bogey’s Cabaret, also known as Popeye’s (locals often used the names interchangeably, as one was upstairs and the other downstairs). The bar was a well-known establishment located in the Prince Rupert Hotel, where people went to unwind after a week of work. The sisters intended to celebrate and meet up with a group of friends that night. The bar was situated along Second Avenue West, on the route Highway 16 takes through downtown Prince Rupert.

Bogey's Cabaret, located at Prince Rupert Hotel in the 1980s (CBC.ca)

Late that night, Alberta’s brother, Francis Williams, recalled receiving a call from Alberta on a payphone outside the bar. Alberta was trying to convince him to come join the party. Alberta was not known as much of a partier and rarely drank, but she was excited to spend her last night in town celebrating with friends and family. Francis remembered her sounding happy and carefree. Despite her request, Francis chose to stay home because he had an early fishing trip planned with their father the next day—one he could not miss.

Claudia did join Alberta that night. When she arrived at Bogey’s, she saw her sister laughing and having a good time with a large group of friends. The bar was crowded, and by the time Claudia arrived, there was nowhere to sit near Alberta. The bar was so packed that they had joined several small tables together to form one long one. Claudia greeted Alberta, then made her way through the bar, watching the band, chatting with friends, and occasionally checking on her sister. She remembers the mood as lighthearted with everyone laughing, dancing, and talking.

At closing time, over 100 bar patrons spilled out onto the streets. Claudia found Alberta outside, laughing with friends. Alberta tried to convince Claudia to come with her to a house party. During their conversation, Claudia’s ex-boyfriend approached, wanting to talk. Claudia told Alberta to wait a moment while she dealt with him, making it clear she had no intention of speaking to him that night. When she turned back, Alberta and the group she had been with were gone.

Claudia waited about 30 minutes for Alberta to reappear outside, then searched the hotel lobby, bathroom, and adjoining streets but found no sign of her sister. Eventually, Claudia went home, comforted by the thought that Alberta was with family or friends and would be safe.

The next morning, Alberta’s mother, Rena, woke to find Alberta’s bed still made. She called Claudia to ask if Alberta was with her, but Claudia reassured her that Alberta probably had a long night and had stayed at a friend’s house. By afternoon, Alberta still hadn’t appeared. By dusk, Francis and Lawrence received a call from Rena saying Alberta had not come home. Rena had called Alberta’s friends, but no one had seen her. Francis and Lawrence reassured her that Alberta would turn up, as they were docking for the night and would return to Prince Rupert the next day.

When Francis and Lawrence returned from their trip on Sunday, Alberta was still missing. Lawrence and Rena went to the local police station to file a missing person report. They knew something was wrong because Alberta was not the type to leave without telling anyone, was not a known partier, had never run away, and most importantly, she had a return ticket to Vancouver she failed to use. Family and friends conducted extensive searches throughout Prince Rupert, and police began investigating and interviewing those who had been at the bar that night.

Three weeks after Alberta disappeared, on September 25th, 1989, her body was found east of Prince Rupert on Highway 16. Hikers crossing a railroad track to a nearby trail discovered the body of a woman lying face down in a ditch covered by shrubs and debris. The body was identified as Alberta’s. The case shifted from a missing person to homicide, as there were obvious signs of a violent struggle. Alberta was found wearing only a blouse and a bra, and it was clear she was very likely a victim of sexual assault.

I mean there is no doubt in my mind that Alberta did whatever she could to get away from whoever it was. She died a horrible death. I mean it is —like, there's no way to minimize it. It's...horrible.Garry Kerr, retired RCMP officer and lead investigator in Alberta's case in 1989 (CBC: Who Killed Alberta Williams?)

Garry Kerr, who worked with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) at the time and was the lead investigator on the case, was transferred to another unit after one year. Since retiring, he has stated that he still thinks about this case because it remains unsolved and believes it can be solved. Kerr believes he knows who killed Alberta, but police were unable to get a search warrant or make an arrest due to lack of evidence. Claudia also believes this man, Alberta's uncle, is responsible for her death.

Claudia recalled that the night Alberta disappeared, she said she was going to a party at her uncle’s house. The man’s wife and son were out of town that weekend, having gone to Gitanyow. He was the last known person to be seen with Alberta. A house guest that night remembered being woken from sleep and seeing multiple people at the house, including Alberta. Geraldine Morrisson, a friend of Alberta’s, recalled Alberta’s uncle acting oddly that night at Bogey’s, more like an overprotective boyfriend than a family member. Garry Kerr also became suspicious of him after police interviews with family and friends, as the man was evasive and became uncooperative after Alberta’s body was found.

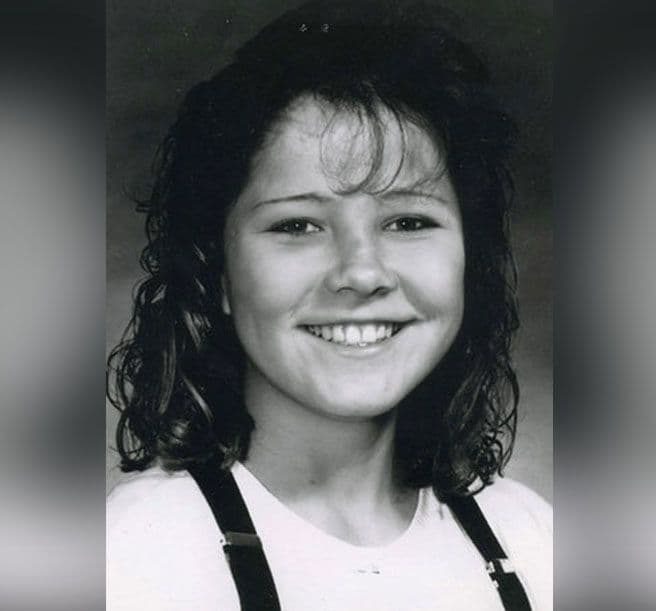

Newspaper clipping of Alberta Williams (CBC.ca)

Some of Alberta’s relatives remembered seeing her the weekend she disappeared. Alberta’s cousin Amanda recalled seeing Alberta in a black pickup truck after the night of her disappearance with her uncle and the boyfriend of Alberta’s youngest sister, Kathy. The trio was seen in Terrace, a town about an hour and a half from Prince Rupert. They stopped by Amanda’s house to use the bathroom and borrow $20 for gas money for the trip back to Prince Rupert. Amanda said Alberta seemed heavily intoxicated and had to be helped out of the truck to use the bathroom. Alberta was seen getting back into the truck, which then drove away, and she was never seen or heard from again. Despite these sightings, this information was never officially reported to the police.

Relationships between the Indigenous community and the RCMP have historically been strained and remain so today. Issues of racism, neglect, brutality, and apathy towards Indigenous people have long existed. The community also carries the painful legacy of residential schooling and the RCMP’s role in it. Many people feared approaching the RCMP and did not trust the institution, which is why many remained silent or were never interviewed in the investigation.

A lot of it had to do, I think with the mistrust of police, and [the feeling that] 'we're native so they're not going to do anything.Garry Kerr, retired RCMP officer and lead investigator in Alberta's case in 1989 (Highway of Tears)

This case remains unsolved, with no arrests or suspects, although it is still actively investigated. Alberta’s family took her body home to Gitanyow, where she was buried next to her sister, Pamela.

Since Alberta's disappearance, a RCMP Task Force called E-PANA was created to investigate the series of unsolved murders along this highway, including Alberta. The purpose of the task force was “to determine if a serial killer, or killers, is responsible for murdering young women traveling along major highways in BC” (E-PANA website). To date, however, this case still remains unsolved, as do all the cases along the highway included in E-PANA. Alberta's family is still searching for answers.